This year we celebrate the 90th anniversary of a film that many of us are lucky to even see. Due to the loss of the original premiere print, many cinephiles could only see enticing snippets of the complete work of the 1927 classic science fiction film Metropolis. I remember, years ago, seeing Metropolis for the first time, and feeling depressed at occasional black spots in the film when title cards were needed to explain what the original film showed. But miraculously, in this past decade alone, incredible steps have been made towards finding scraps of negatives and prints, slowly piecing together and rescuing what was once a sad patchwork of scenes. With this 90th anniversary screening, we celebrate the remarkable achievement that is The Complete Metropolis. But that’s the post-release history, and as astonishing as it is, the true accomplishment still belongs to the creators of Metropolis, and the majesty of the film itself.

The story begins over a hundred years ago, with a renaissance of avant-garde films emerging from Germany. Due to restrictions on imported foreign films during the First World War, a high demand for domestic German films developed, resulting in a series of innovative German art films that continued far into the interwar years. This movement would become known as German Expressionist cinema, famous for its illustration of subjective emotions through powerful set design, dynamic manipulation of shadows and light, expressive silent acting and

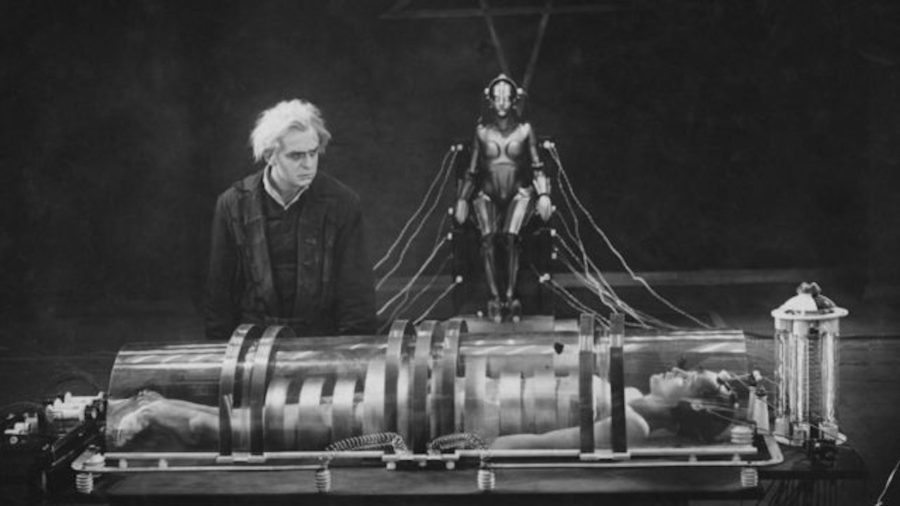

If you’ve seen C-3PO, you’ve seen the Machine-Man. The resemblance is not accidental. Built by the wonderfully Frankenstein-esque inventor Rotwang, the Machine-Man illustrates the Futurist theme of the film. Where the ancient people built a Tower to Heaven, the people of the future build an android that perfectly mimics humanity. Originally the machine was built by Rotwang to bring his beloved wife back to life, but the forces hoping to stop Maria’s preachings command Rotwang to use the Machine-Man to instead mimic Maria and distort her message to the people. In this we see a corruption of the Futurist ideal. The Futurist movement argued that machines should be celebrated as a positive step by humanity towards a better tomorrow, but here we see it taken by the capitalist (and humorously Satanic) forces and turned into a weapon against humanity. The machine is transformed into an abomination by man’s greed and cruelty.

Metropolis remains relevant after ninety years because (astonishingly and despite everything) not much has changed in ninety years. Issues like anxiety over machines replacing workers, workers being treated like machines, extreme economic inequality and social tensions erupting into violence on the streets are all still relevant. Metropolis boldly and concisely takes these issues and drops them into an astonishing melting pot of Futurist, Expressionist, Gothic, Biblical and science fictional imagery. It is a masterpiece that has influenced everyone from Ridley Scott to Janelle Monae, so if you are one of the few incredibly lucky people who can see it on the big screen with surround sound, please take the opportunity while you can. Especially now, during the occasion of its 90th anniversary.

Metropolis is having a 90th anniversary screening at York’s CityScreen Picturehouse on Monday 16th November 2017.

(Review written for Metropolis’s 90th Anniversary for student newspaper)