Canada has a culture problem. As a nation with two mother languages, English and French, it is overwhelmed by the cultural monoliths of the USA and France. When Hollywood is so close, why should Canadian artists stay in their native land when fame and wealth lie just below the border? And even when films are made in Canada, how are they any different to the styles and genres of the USA and France? To find the Canadian-ness of Canadian films, this article will be examining the work of one of Canada’s most prolific and distinctive filmmakers: David Cronenberg.

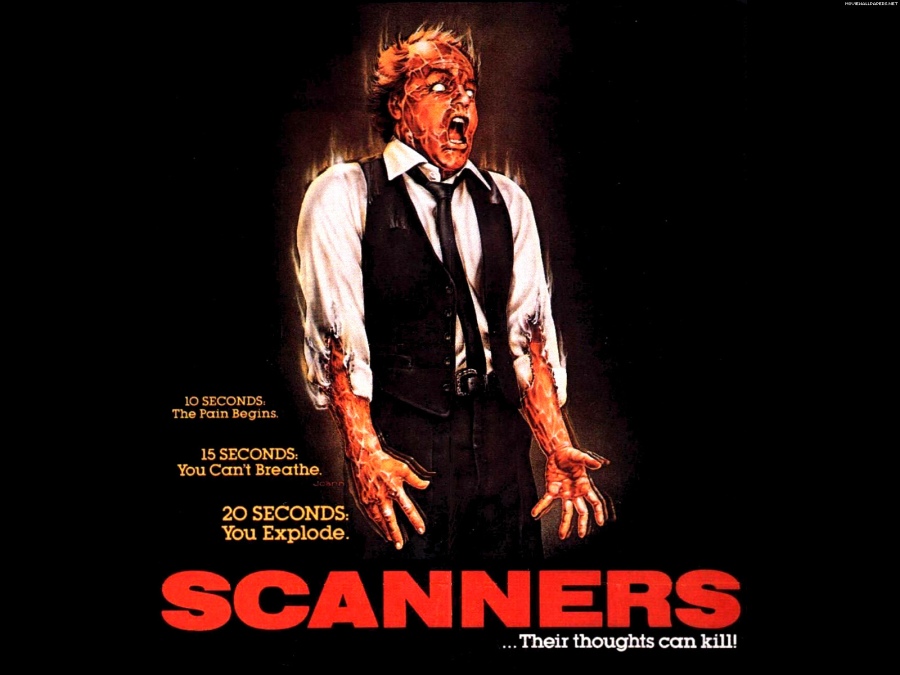

Cronenberg is a unique artist to explore in relation to Canada. Beginning in the 1970s as a genre director with a penchant for gore and body horror, Cronenberg’s films were initially considered an embarrassing footnote of Canadian film by critics and social commentators. Who was this director, deliberately shocking the public with images of parasites crawling out of stomachs, and heads exploding from telepathic mind control; and worse than that, how dare he use public money to produce them? Due to the fact that his debut films Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977) looked akin to the cheap exploitation films of American director and producer Roger Corman; Cronenberg received further criticism. Not only did the films appear cheap and exploitative, they seemed more “American” than “Canadian.” But during this same period, Cronenberg was already beginning to find an audience.

What was becoming apparent, especially with The Brood (1979) and Scanners (1981), was that Cronenberg’s films had an authorial vision behind them. Thanks to the lack of big-studio influence by working within the Canadian film industry, Cronenberg was able to present the world in the disturbing manner in which he viewed it. He observes society so impersonally that it feels incredibly realistic and extraordinarily empty. There is an unsettling blandness to the worlds of these early films. Buildings are grey and beige, people are grey and beige, and everywhere is cold. With no big name actors and everyday wardrobes, few of the characters stand out physically. Cronenberg’s emotionless vision of humanity recreates Canada as uniform, corporate and suffocating.

It was what was behind these strained social niceties that fascinated him. While The Brood tells the story of murderous child-mimicking gremlins created by a disturbed woman’s psychosis, Scanners follows an underclass of telepaths, whose freakish abilities are hidden within their own heads. In both films you have middle class suburbia disturbed by an alien menace; one that takes violent revenge upon “normalcy” but actually originates from that same suburbia’s seemingly healthy psyche. It is in how Cronenberg frames these phenomena, through board meetings, doctor appointments and police autopsies, that the viewer is both engrossed by the minutia of clinical detail and equally alienated by the inhumanity of it.

The telepathic “Scanners” in Scanners may be socially awkward and creepy, but their humanity shines through greater than the expositing doctors and corporate men that control them. In his breakout role, Canadian actor Michael Ironside steals the film as villainous telepath Darryl Revok, the viewer feeling his passionate rage as he attempts to unite fellow scanners to declare war on the less evolved, non-telepathic human race. He also causes a man’s head to explode, which while horrifying, is blackly comic (another feature of Cronenberg’s transgressive style).

The Brood and Scanners are also the debut films of Canadian composer Howard Shore, whose music perfectly captures the horror of modern life with piercing string music, finding horror even in civil mundanity. It is easy to draw a line between these scores and the later unsettling music he composed for The Silence of the Lambs (1991). Scanners is not Cronenberg’s most successful film but it, along with The Brood, does convey his own personal alienation from the human body and from modern day civilities (whether those be familial estrangement or board room meetings). An intense and disturbing alienation from the ugliness of urban humanity, whom are depicted as a microcosm of deformed, diseased and bloody bodies, with minds on the verge of mental breakdown and all too ready to snap.

Unpublished student magazine article, 2018